2 The Budget of the Universe

Three kilometers below the surface of South Africa, in rock sealed from sunlight for perhaps twenty million years, a bacterium called Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator may divide as rarely as once per century. Its energy source is hydrogen gas, produced atom by atom as uranium in the surrounding rock decays. Its electron acceptor is sulfate, trapped in mineral inclusions since the Archean. The reaction releases just enough free energy to synthesize a handful of ATP molecules—just barely enough to copy a genome, repair a membrane, and divide.1

This organism runs on one of the thinnest energy budgets yet measured in the biosphere. To understand how it survives—how any microbe survives—you need to understand what “energy budget” means. That requires physics. Not all of physics. Just the rules that govern what reactions can happen, how much energy they release, and why some reactions proceed while others, equally favorable on paper, sit frozen until the right catalyst arrives.

In February 1943, a physicist who had already changed the world once sat down to give a series of lectures at Trinity College, Dublin. Erwin Schrödinger was fifty-five, exiled from Austria, and restless. He had won the Nobel Prize a decade earlier for an equation that described how matter behaves at atomic scales. Now he wanted to ask a question that no physicist had any business asking:

What is life?

Not what life is made of—biochemists were sorting that out. Not where life came from—that was still anyone’s guess. Schrödinger wanted to know what physical rules a living system must obey simply to persist. He looked at biology and saw thermodynamics. The lectures became a slim book, published in 1944, and the book became one of the most influential scientific texts of the twentieth century.23

Schrödinger’s argument was almost unsettling in its clarity. Living systems maintain internal order—precise molecular arrangements, concentration gradients, structured membranes—in a universe that relentlessly erases differences. The Second Law of Thermodynamics says that the total disorder of a closed system can only increase. So how does a bacterium, a fern, or a physicist stay organized?

Not by violating the Second Law. By obeying it creatively. A living organism maintains its internal order by exporting disorder—entropy—to the surroundings. It takes in structured energy (food, sunlight) and releases degraded energy (heat, waste). The organism stays organized; the universe, on balance, becomes more disordered. The accounting always works out.

Schrödinger also made a second, remarkably prescient prediction. He argued that the genetic material—whatever it was—must be a stable, information-bearing structure. He called it an “aperiodic crystal”: not a repeating lattice like salt or diamond, but an irregular arrangement capable of encoding instructions. Nine years later, Watson and Crick described the double helix of DNA.4 It was, almost exactly, Schrödinger’s aperiodic crystal.

But this chapter is not about DNA. It is about the first half of Schrödinger’s insight: the energy rules. Before there was life, before there was an ocean, before there was a planet with liquid water, there were the laws of thermodynamics and quantum mechanics. These laws—discovered in European laboratories with hydrogen atoms, metal plates, and vacuum tubes—constrain every chemical reaction, every metabolic pathway, and every living organism.

They are the budget of the universe—the same rules that keep D. audaxviator alive three kilometers underground, harvesting hydrogen atoms released one at a time by radioactive decay.

2.1 Energy in packets

The story begins in 1900, with a problem about light.

Physicists at the time understood that hot objects glow. Heat a piece of iron and it radiates: first a dull red, then orange, then white. The spectrum of this radiation—how much energy comes out at each wavelength—had been measured precisely. But no one could explain it. The best theoretical predictions diverged from the data at short wavelengths, predicting infinite energy where experiments showed almost none. This embarrassment became known as the “ultraviolet catastrophe.”5

Max Planck found the fix by making an assumption he didn’t entirely believe. He proposed that energy is not emitted continuously, like water from a hose, but in discrete packets—quanta—whose size depends on frequency:

\[ E = h\nu \]

Here \(\nu\) is the frequency of the radiation and \(h\) is a new constant of nature, now called Planck’s constant (\(h \approx 6.626 \times 10^{-34}\) J\(\cdot\)s).6 The constant is extraordinarily small, which is why the graininess of energy is invisible in everyday life. But at atomic and molecular scales, it is everything.

A chlorophyll molecule absorbs red light at around 680 nm because the energy of a red photon (\(E = h\nu = hc/\lambda\)) matches a specific electronic transition in chlorophyll.7 A photon of slightly lower energy, in the infrared, cannot make that jump. A photon of much higher energy, in the ultraviolet, would overshoot and cause damage. The quantization of energy is why biology runs on specific wavelengths and not on a continuous smear. Cyanobacteria—the microbes that invented oxygenic photosynthesis roughly 2.5 billion years ago—exploit exactly this specificity. Their chlorophyll absorbs red photons at 680 nm because that is where the electronic transition sits; a few nanometers in either direction and the reaction center would be blind.

Five years after Planck’s proposal, Albert Einstein pushed the idea further. He showed that light itself behaves as a stream of particles—photons—each carrying exactly one quantum of energy \(E = h\nu\). His evidence came from the photoelectric effect: when light strikes a metal surface, it can knock electrons free, but only if each individual photon carries enough energy to overcome the binding force that holds the electron in the metal.8 Below a threshold frequency, nothing happens—no matter how bright the light. Above it, electrons fly out immediately. The energy of the ejected electrons increases linearly with the frequency of the incoming light, exactly as \(E = h\nu\) predicts. Einstein received the Nobel Prize for this work in 1921, not for relativity.

Chemical bonds have specific energies. Breaking them requires a minimum energy input. Forming new bonds releases specific amounts of energy. None of this would work if energy were continuous. In anoxic sediments, methanogens harvest dissolved hydrogen to reduce CO\(_2\) to methane—a reaction whose standard free-energy yield is modest and whose actual yield depends sharply on local hydrogen concentration. Four molecules of H\(_2\) enter the reaction, so the energy available scales with the fourth power of hydrogen activity. At the nanomolar concentrations typical of real sediment, the margin between a viable metabolism and a thermodynamic dead end is vanishingly thin.

2.2 The hydrogen-chlorine cannon

To see what quantized energy means in practice, consider a demonstration that could have come from a nineteenth-century lecture hall—and occasionally did, with spectacular results.

Mix hydrogen gas and chlorine gas in a sealed tube. At room temperature, nothing happens. The molecules drift past each other, colliding but not reacting. The reaction \(\text{H}_2 + \text{Cl}_2 \rightarrow 2\text{HCl}\) is thermodynamically favorable; the products are lower in energy than the reactants. But “favorable” and “spontaneous” are not the same thing. There is a barrier in the way.

The barrier is the Cl–Cl bond. Before hydrogen and chlorine atoms can rearrange into HCl, the chlorine molecule must first be broken apart. That costs energy. How much? The bond dissociation energy of Cl\(_2\) is 242 kJ/mol. The H–H bond is stronger: 436 kJ/mol. Each new H–Cl bond that forms releases 431 kJ/mol.9

The overall energy balance:

\[ \Delta H = \underbrace{(436 + 242)}_{\text{bonds broken}} - \underbrace{2 \times 431}_{\text{bonds formed}} = -184 \text{ kJ/mol} \]

The reaction releases 184 kJ of heat for every mole of H\(_2\) consumed. It is exothermic—it releases energy that can do useful work.

But to get started, someone has to pay the activation cost: breaking that first Cl–Cl bond. Convert to the energy per single bond:

\[ E_{\text{bond}} = \frac{242 \times 10^3}{6.022 \times 10^{23}} = 4.02 \times 10^{-19} \text{ J} \]

Now ask: what wavelength of light carries exactly this much energy per photon?

\[ \lambda = \frac{hc}{E} = \frac{(6.626 \times 10^{-34})(3.0 \times 10^8)}{4.02 \times 10^{-19}} \approx 494 \text{ nm} \]

That is blue light. Shine a red lamp at the mixture and nothing happens—each photon is too feeble to snap a Cl–Cl bond. Shine a blue or violet lamp and the reaction ignites. Once a few Cl–Cl bonds break, the released chlorine atoms attack H\(_2\) molecules, which starts a chain reaction. The temperature in the tube can soar by thousands of kelvins; the pressure can spike above 20 atmospheres. The tube becomes a cannon.

This is quantization in action. The reaction is favorable, the reactants are mixed, and yet nothing happens until a photon of the right energy arrives to pay the activation cost. Red light is too cheap. Blue light is expensive enough. The threshold is absolute — below it, nothing happens.

Every reaction in biochemistry follows the same logic. Enzymes do not change whether a reaction is favorable; they lower the activation barrier so that the reaction can proceed at body temperature. They are, in effect, a substitute for the blue lamp—a way to start the cannon without the explosion.

D. audaxviator carries hydrogenase enzymes that lower the barrier for oxidizing H\(_2\) with sulfate. Without those enzymes, the reaction would be thermodynamically favorable but kinetically frozen, like a hydrogen-chlorine mixture sitting in the dark. The enzyme is the lamp.

2.3 The budget: Gibbs free energy

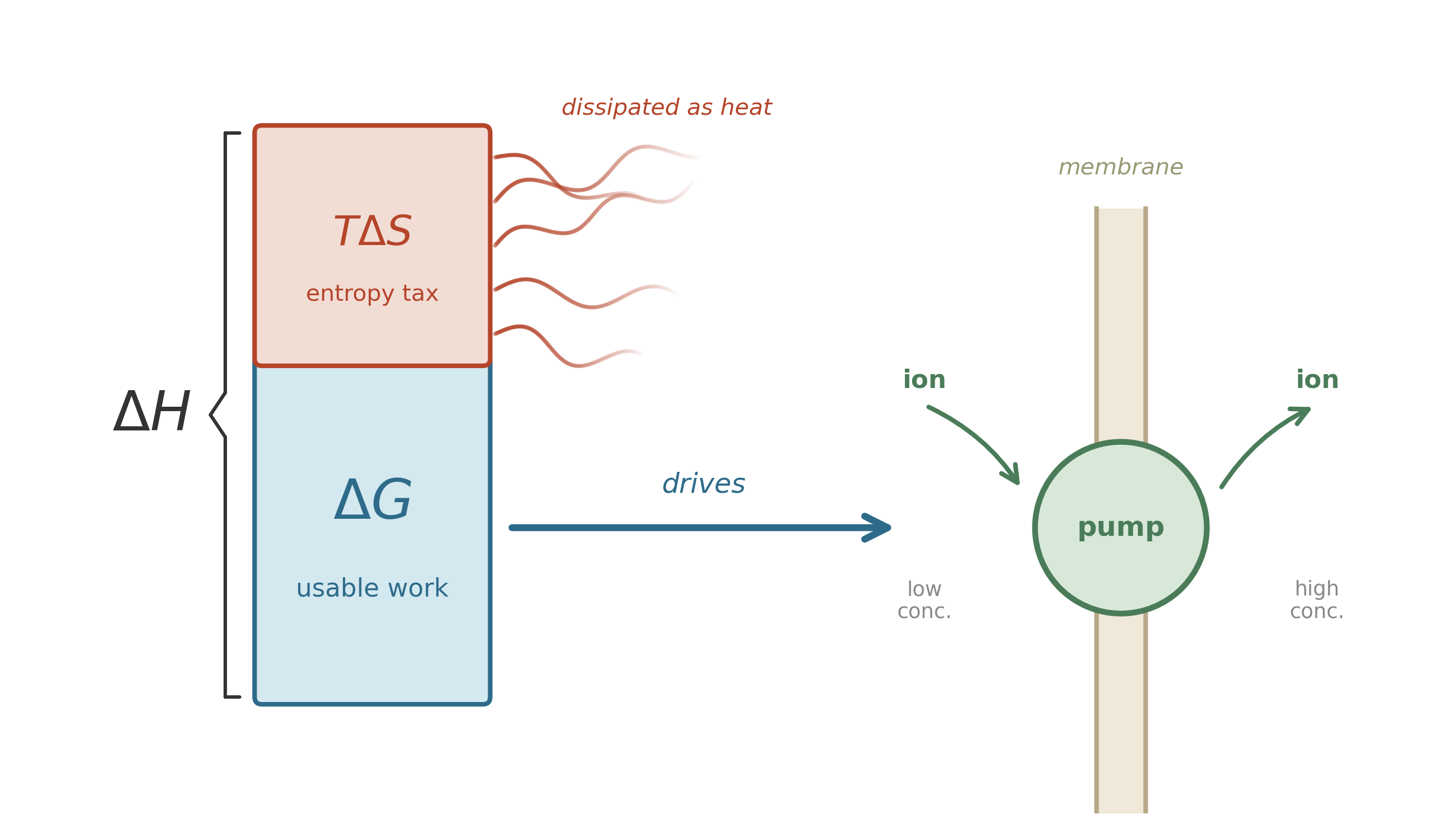

In a marine sediment, a sulfate reducer and a methanogen may both have access to the same pool of dissolved hydrogen—but only the organism whose reaction yields usable energy under local conditions gets to grow. The hydrogen-chlorine cannon illustrates the distinction that decides the winner: the difference between energy that is released and energy that is available to do work. Not all released energy is useful. Some of it dissipates as disordered heat. Some of it goes into rearranging the surroundings in ways you cannot harness. To understand what a reaction can actually accomplish—whether it can build a molecule, pump an ion across a membrane, or power a flagellar motor—you need a sharper accounting tool.

That tool was invented by Josiah Willard Gibbs in the 1870s, and it is the equation that appears more often than any other in this book.10

\[ G = H - TS \]

Read it as a budget. \(H\) is enthalpy—roughly, the total energy content of the system (heat plus pressure-volume work). \(T\) is temperature. \(S\) is entropy—a measure of disorder, or more precisely, the number of microscopic arrangements consistent with the macroscopic state. The product \(TS\) is the energy that has been “claimed” by disorder: energy that is spread out so evenly it can no longer drive anything in a particular direction.

\(G\), the Gibbs free energy, is what remains. It is what you can actually spend.

When a reaction occurs, the change in Gibbs free energy tells you the direction:

- If \(\Delta G < 0\): the reaction can proceed spontaneously. It releases usable energy.

- If \(\Delta G > 0\): the reaction requires an input of energy. It will not happen on its own.

- If \(\Delta G = 0\): the system is at equilibrium. No net change occurs.

Think of enthalpy as gross income and \(TS\) as the tax the universe collects; \(G\) is what remains to spend on maintenance, growth, or reproduction.

Microbes do not optimize. They cover costs. A bacterium in a sediment pore does not search for the reaction with the largest \(\Delta G\); it runs whatever reaction its existing enzymes can catalyze, provided the return exceeds the minimum cost of staying alive. In the language of decision theory, microbes satisfice: they find strategies that are good enough, not strategies that are best.11 This distinction – between optimizing and satisficing – explains a pattern visible in every marine sediment core: the redox zones overlap instead of forming sharp boundaries, and supposedly outcompeted metabolisms persist in the “wrong” zone. Optimization models predict sharp exclusion. Satisficing models predict the fuzzy coexistence and apparent inefficiency that field measurements consistently show. The physics sets the menu. The microbes choose what they can afford, not what is cheapest.

2.3.1 Real conditions, not standard ones

The standard Gibbs energy \(\Delta G^\circ\) is a reference point, measured under a specific set of conditions (typically 1 mol/L concentrations, 1 atm pressure, 25\(^\circ\)C). Real environments are nothing like this. A bacterium in a sediment pore faces concentrations that are orders of magnitude different from standard conditions. To know the actual energy available, you need the master equation:

\[ \Delta G = \Delta G^\circ + RT \ln Q \]

Here \(R\) is the gas constant (8.314 J mol\(^{-1}\) K\(^{-1}\)), \(T\) is absolute temperature, and \(Q\) is the reaction quotient—the ratio of product activities to reactant activities, each raised to the power of its stoichiometric coefficient.

The reaction quotient captures how concentrations shift the energy balance. When products accumulate, \(Q\) increases, and \(\Delta G\) becomes less negative: less energy is available. When reactants are abundant, \(Q\) is small, and there is more energy to harvest. At equilibrium, \(Q\) equals the equilibrium constant \(K_{\text{eq}}\), and \(\Delta G = 0\):

\[ \Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln K_{\text{eq}} \]

This is not a separate equation. It is a special case of the one above, evaluated at the point where the reaction has no net tendency to move in either direction.

For biochemical reactions, a modified convention is often used: \(\Delta G^{\circ\prime}\), where the prime indicates standard conditions at pH 7 rather than the chemist’s convention of pH 0. Since most biology operates near neutral pH, this keeps the reference point close to reality.12

Two guilds compete for dissolved H\(_2\) in marine sediment: sulfate reducers and methanogens. Their net reactions:

Sulfate reduction:

\[4\text{H}_2 + \text{SO}_4^{2-} + 2\text{H}^+ \longrightarrow \text{H}_2\text{S} + 4\text{H}_2\text{O} \qquad \Delta G^{\circ\prime} \approx -152 \text{ kJ/mol}\]

Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis:

\[4\text{H}_2 + \text{CO}_2 \longrightarrow \text{CH}_4 + 2\text{H}_2\text{O} \qquad \Delta G^{\circ\prime} \approx -131 \text{ kJ/mol}\]

Both are exergonic at standard conditions, but in real sediment \(Q\) does the work. As microbes consume H\(_2\), its concentration drops and \(Q\) rises, making \(\Delta G\) less negative. Each guild has a minimum energy yield—roughly \(-10\) to \(-20\) kJ/mol, the cost of pumping a single ion across a membrane—below which it cannot sustain its energy-conserving machinery.13

Because the methanogen’s \(\Delta G^{\circ\prime}\) is smaller to begin with, its \(\Delta G\) crosses the viability threshold at a higher H\(_2\) concentration. Field measurements confirm the prediction: sulfate reducers draw H\(_2\) down to roughly 1–1.5 nM; methanogens stall at roughly 7–10 nM.14 Where sulfate is available, sulfate reducers pull H\(_2\) below the methanogen’s threshold and win by default. Methanogens dominate only where sulfate is exhausted and no one else is pulling H\(_2\) lower.

This is not a hand-waving story. Plug the concentrations into \(\Delta G = \Delta G^{\circ\prime} + RT \ln Q\), and the guild boundaries fall out of the arithmetic. The physics predicts the zonation; the microbes confirm it.

A powerful shortcut for estimating how much free energy an organic molecule contains: look at the average oxidation state of its carbon atoms.

Methane (CH\(_4\)) is the most reduced single-carbon compound. Each carbon is surrounded by hydrogen; the oxidation state is \(-4\). Carbon dioxide (CO\(_2\)) is fully oxidized: oxidation state \(+4\). When an organism oxidizes methane all the way to CO\(_2\), it extracts the maximum possible energy from that carbon atom.

Most organic molecules fall between these extremes. Glucose (C\(_6\)H\(_{12}\)O\(_6\)) has an average carbon oxidation state of 0. Fatty acids, with their long hydrocarbon chains, are more reduced (roughly \(-2\) per carbon) and carry more energy per carbon. Carboxylic acids are more oxidized and carry less.

The insight is practical: the oxidation state of the carbon atoms in an organic molecule provides a direct measure of its free-energy content.15 You do not need to look up \(\Delta G_f^\circ\) for every compound. A quick glance at the molecular formula tells you whether the molecule is energy-rich or energy-poor.

In any sediment core, the reactivity of organic carbon drops with depth—a pattern that is, at bottom, an oxidation-state story. The “freshness” of buried organic material tracks its average oxidation state.

2.4 Why energy levels are discrete

The discreteness of energy levels—why atoms have specific orbitals and bonds have specific strengths—traces back to the wave nature of matter. Particles themselves behave as waves, confirmed experimentally in the 1920s and formalized by the Schrödinger equation. Electrons confined to an atom cannot have arbitrary energies, for the same reason a guitar string cannot vibrate at arbitrary frequencies: the boundary conditions select only certain standing-wave patterns, and each pattern corresponds to a specific energy. The full derivation, along with the hierarchy of electronic, vibrational, rotational, and translational energy modes in molecules, is developed in Appendix D.

2.5 Chemical equilibrium and the reaction quotient

We have assembled the pieces: energy comes in quanta, bonds have specific energies, and the Gibbs free energy tracks how much usable work a reaction can deliver. Now we can formalize chemical equilibrium.

Every chemical species in a mixture has a chemical potential \(\mu_i\)—a measure of how much the system’s free energy would change if you added one more mole of that species. For an ideal system:

\[ \mu_i = \mu_i^\circ + RT \ln a_i \]

where \(\mu_i^\circ\) is the standard chemical potential and \(a_i\) is the activity of species \(i\) (roughly, its effective concentration, corrected for non-ideal behavior). When activities are moderate and solutions are dilute, activities are often approximated by concentrations, which is what we will do in most of this book. The appendix on the Energy Toolkit discusses when and why that approximation breaks down.16

The reaction quotient \(Q\) for a general reaction \(a\text{A} + b\text{B} \rightleftharpoons c\text{C} + d\text{D}\) is:

\[ Q = \frac{a_{\text{C}}^c \cdot a_{\text{D}}^d}{a_{\text{A}}^a \cdot a_{\text{B}}^b} \]

Plugging the chemical potentials into the Gibbs energy expression gives us back the master equation:

\[ \Delta G = \Delta G^\circ + RT \ln Q \]

At equilibrium, \(\Delta G = 0\). The system has no net tendency to shift in either direction. The reaction quotient at this point equals the equilibrium constant:

\[ Q_{\text{eq}} = K_{\text{eq}} \]

and therefore:

\[ \Delta G^\circ = -RT \ln K_{\text{eq}} \]

This equation bridges thermodynamic tables and observable chemistry. It connects the standard free energy change (which you can look up in tables or calculate from bond energies) to the equilibrium constant (which tells you how far a reaction will go before it stops). A large negative \(\Delta G^\circ\) means a large \(K_{\text{eq}}\): the reaction strongly favors products. A \(\Delta G^\circ\) near zero means the reaction is easily reversible and sensitive to conditions.

For microbial metabolism, the critical quantity is rarely \(\Delta G^\circ\). It is \(\Delta G\)—the energy available right here, right now, at the actual concentrations in the local environment. Two identical reactions can have completely different \(\Delta G\) values in different environments, because \(Q\) depends on what has been consumed and what has accumulated. A reaction that yields energy near the sediment surface, where oxygen is present, may cost energy a centimeter deeper, where oxygen has been depleted.

The concentration profiles in a sediment column—oxygen dropping to zero, sulfate declining, methane appearing—are the visible signatures of \(Q\) shifting through space, dragging \(\Delta G\) with it. Each zone is dominated by a different microbial guild: aerobic heterotrophs at the top, sulfate reducers in the middle, methanogens at the bottom. The physics sets the order. The microbes fill the niches.

2.6 The rules before the game

Planck showed that energy comes in packets. Einstein showed that light carries these packets as particles. The wave nature of matter — confirmed experimentally in the 1920s and formalized by the Schrödinger equation — explains why atoms and molecules have discrete energy levels. From those energy levels come bond energies, activation barriers, and the electronic transitions that make photosynthesis and respiration possible.

Gibbs, working half a century before quantum mechanics, already had the thermodynamic framework: enthalpy minus the entropy term gives you the free energy. With the reaction quotient \(Q\) adjusting for local conditions, you can calculate the energy available from any reaction in any environment.

The rules they uncovered—quantized energy, Gibbs free energy, chemical equilibrium—are the same rules that govern every metabolic reaction in every living cell that has ever existed. They governed the first autocatalytic cycles in hydrothermal vents 4 billion years ago.17 They govern the sulfate-reducing bacteria 3 kilometers underground in a South African gold mine today.18 Evolution operates within the Second Law, not outside it. Natural selection can explore an enormous space of molecular strategies, but every strategy must close the Gibbs ledger: find a reaction with \(\Delta G < 0\) under local conditions, harvest that energy, and export the resulting entropy.

D. audaxviator, three kilometers underground, obeys every rule in this chapter. So does every other organism we will meet. The rules were set before the first cell divided.

2.7 Takeaway

- Energy comes in discrete packets (\(E = h\nu\)), which is why specific photons break specific bonds and why photosynthesis requires specific wavelengths.

- The Gibbs free energy \(G = H - TS\) is the universal constraint: enthalpy minus the entropy cost gives the energy available to do work.

- Under real conditions, \(\Delta G = \Delta G^\circ + RT \ln Q\) adjusts for actual concentrations. At equilibrium, \(\Delta G = 0\) and the reaction quotient equals \(K_{\text{eq}}\).

- Wave-particle duality (Appendix D) explains why energy levels are discrete and why bonds have the strengths they do. Molecules store energy in electronic, vibrational, rotational, and translational modes.

- These rules—discovered with hydrogen atoms and metal plates—are the same rules that will govern every bacterium, every enzyme, every metabolic pathway for the next 4.5 billion years of Earth’s history.

Li-Hung Lin et al., “Long-Term Sustainability of a High-Energy, Low-Diversity Crustal Biome,” Science 314 (2006): 479–482. (Lin et al. 2006)↩︎

Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell (Cambridge University Press, 1944). (Schrödinger 1944)↩︎

The three lectures were delivered 5, 12, and 19 February 1943 at Trinity College Dublin. See Erwin Schrödinger, What Is Life? (Cambridge University Press, 1944), preface. (Schrödinger 1944)↩︎

James D. Watson and Francis H. C. Crick, “Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid,” Nature 171 (1953): 737–738. (Watson and Crick 1953)↩︎

Max Planck, “Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum,” Annalen der Physik 309, no. 3 (1901): 553–563. (Planck 1901)↩︎

Fundamental constants from Eite Tiesinga et al., “CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2018,” Reviews of Modern Physics 93 (2021): 025010. (Tiesinga et al. 2021)↩︎

680 nm refers to the P680 reaction center of Photosystem II; chlorophyll a in solution absorbs maximally at ~664 nm. See Robert E. Blankenship, “Early Evolution of Photosynthesis,” Plant Physiology 154 (2010): 434–438. (Blankenship 2010)↩︎

Albert Einstein, “Concerning an Heuristic Point of View Toward the Emission and Transformation of Light” (1905). (Einstein 1905)↩︎

Bond dissociation energies from William M. Haynes, ed., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 93rd ed. (CRC Press, 2012). (Haynes 2012)↩︎

Willard Gibbs, “A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces” (1873). (Gibbs 1873)↩︎

Herbert A. Simon, “Rational Choice and the Structure of the Environment,” Psychological Review 63 (1956): 129–138. (Simon 1956)↩︎

Gerald Karp, Cell and Molecular Biology: Concepts and Experiments, 7th ed. (Karp 2008)↩︎

Tori M. Hoehler, “Biological Energy Requirements as Quantitative Boundary Conditions for Life in the Subsurface,” Geobiology 2 (2004): 205–215. The minimum biological energy quantum—the smallest energy yield that can drive ion translocation across a membrane—is approximately \(-20\) kJ/mol (Schink 1997), though field measurements suggest methanogens can operate at yields as small as \(-10\) kJ/mol. (Hoehler 2004)↩︎

Derek R. Lovley and Steve Goodwin, “Hydrogen Concentrations as an Indicator of the Predominant Terminal Electron-Accepting Reactions in Aquatic Sediments,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 52 (1988): 2993–3003. (Lovley and Goodwin 1988)↩︎

The oxidation-state framework for organic carbon is developed in Werner Stumm and James J. Morgan, Aquatic Chemistry, 3rd ed. (Wiley, 1996), ch. 8. (Stumm and Morgan 1996)↩︎

Peter Atkins and Loretta Jones, Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight (2010). (Atkins and Jones 2010)↩︎

William Martin and Michael J. Russell, “On the Origins of Cells,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 358 (2003): 59–85. (Martin and Russell 2003)↩︎

Li-Hung Lin et al., “Long-Term Sustainability of a High-Energy, Low-Diversity Crustal Biome,” Science 314 (2006): 479–482. (Lin et al. 2006)↩︎