3 The Stage

Three planets formed from the same cloud of dust.

They orbited the same young star, caught roughly the same rain of water and carbon, and obeyed identical physics. If you had visited the inner solar system 4.5 billion years ago, you would have had trouble telling them apart: three balls of molten rock, each venting steam into a thin, violent atmosphere, each bombarded by leftover debris. The raw materials were almost identical. The thermodynamic rules–established in the previous chapter–were exactly the same.

And yet, within a billion years, one of those planets was alive, another was a furnace, and the third was a frozen desert.

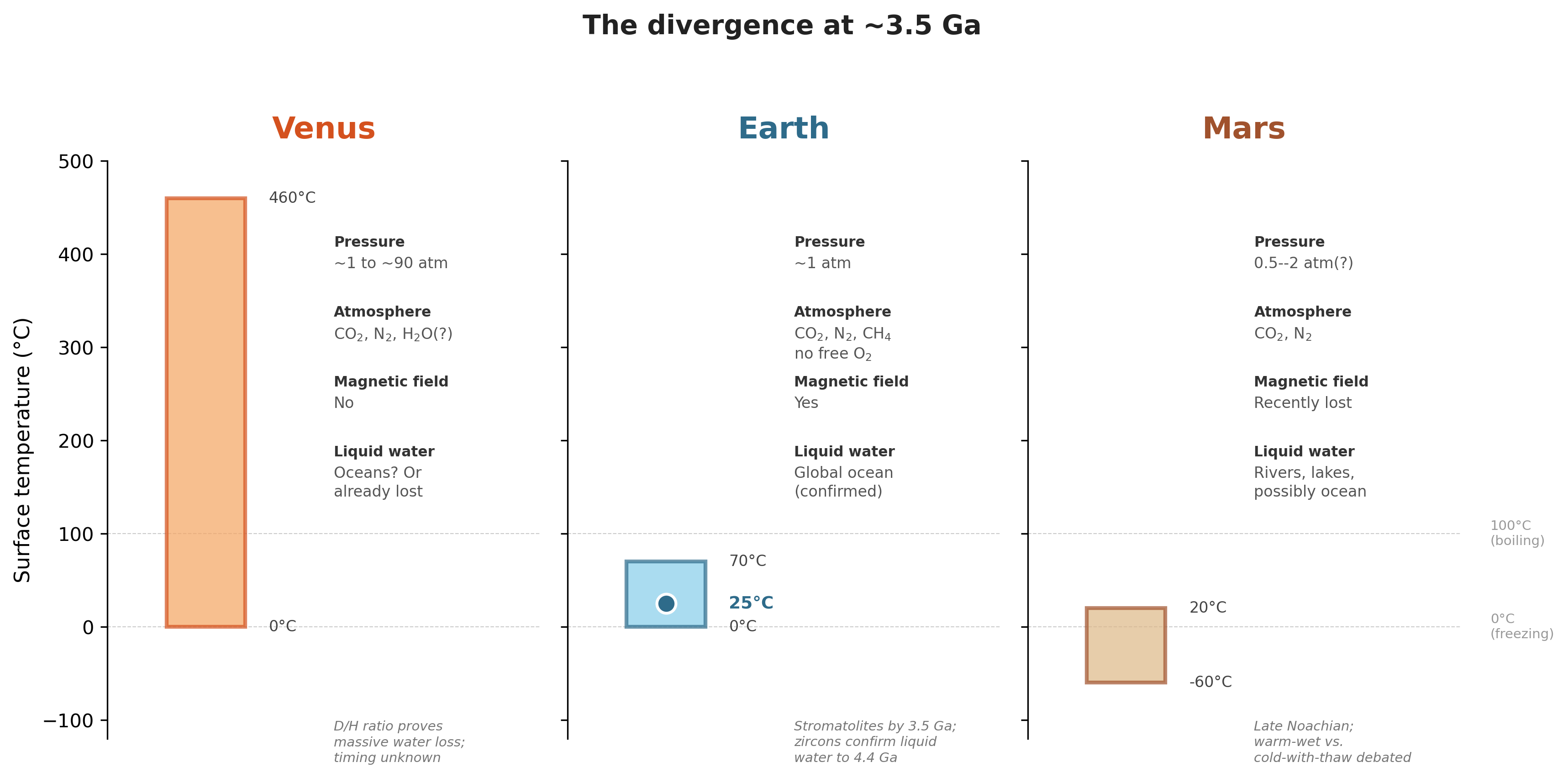

Look at the uncertainty bars. Earth is the best-known case: three independent proxies—rock structures,1 mineral isotopes,2 and reconstructed ancient enzymes3—converge on a surface temperature near 25°C. Venus and Mars are far less constrained. Deuterium ratios prove Venus lost its water,4 but when?5 Mars’s crustal magnetism proves an early dynamo,6 but warm-wet or cold-episodic?7 Same raw materials, same physics, three different outcomes.

What sequence of physical accidents turned one ordinary rocky planet into the one place where non-equilibrium chemistry could build a biosphere? The answer is not a single miracle. It is a chain of contingencies–each one physical, each one measurable, and each one specific enough to test.

3.1 The violence that built the world

The solar system did not assemble gently. It condensed from a disk of gas and dust around a young star, and the condensation was competitive. Small grains stuck together into pebbles, pebbles into boulders, boulders into planetesimals tens of kilometers across. Those planetesimals collided, shattered, reformed, and collided again. The inner solar system, where temperatures were too high for ices to survive, produced rocky bodies: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and a great deal of rubble that didn’t make it into a planet at all.

The process was not orderly. It was a series of collisions in which the survivors were simply the bodies that absorbed the most impacts without fragmenting. Earth accreted over tens of millions of years, each impact delivering kinetic energy that converted to heat on arrival. The growing planet was partly or entirely molten for much of this period–a magma ocean hundreds of kilometers deep, with an atmosphere of rock vapor and steam above it.

Venus and Mars went through the same process. So did a number of other bodies that no longer exist as independent planets, because they were absorbed or ejected. The starting chemistry was not special. All three surviving inner planets received water vapor, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, sulfur compounds, and a grab-bag of metals delivered by the same population of impactors. The differences that would later matter–the differences between a dead world and a living one–were not written into the ingredients. They emerged from the physics of what happened next.

The first 700 to 800 million years of Earth’s history left almost no direct record in the crust. The oldest surviving minerals–tiny crystals of zircon from Western Australia–are about 4.4 billion years old. Everything before that was recycled: melted, subducted, destroyed by impacts, or simply overwritten by the planet’s own geological activity. This period, the Hadean eon, is named after the Greek underworld, and the name is apt. We know the Earth existed. We know it was hot. We know it was hit, repeatedly, by objects large enough to re-melt the surface. But we have almost no rocks from that time to read.8

What we do have is physics. And physics, combined with isotope geochemistry and careful modeling, lets us reconstruct quite a lot from very little direct evidence.

3.2 The blow that made the Moon

Sometime during the first hundred million years, Earth was struck by another planet.

Not a small asteroid. Not a glancing blow. A body roughly the size of Mars–or possibly larger–collided with the young Earth in an impact so violent that it partially vaporized both objects. The debris from this collision–a disk of molten and vaporized rock orbiting what remained of Earth–coalesced – perhaps within centuries, perhaps faster – into a new body: the Moon.9

The evidence for this is not speculative. The Moon’s bulk composition is strikingly similar to Earth’s mantle (not to the average solar system), which means it formed from Earth material. The Moon is depleted in volatile elements, consistent with formation from a superheated debris disk. The angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system is consistent with a giant impact. And the Moon is large relative to its planet–unusually large–which is hard to explain by capture but straightforward if it was born from the planet itself.

What did this catastrophe give us?

First, it gave Earth a fast spin. The impact transferred enormous angular momentum, and the young Earth may have rotated with a day as short as five or six hours. Over billions of years, tidal interaction with the Moon has slowed this rotation to our current 24-hour day. But the important thing is that the day-night cycle existed from the start: a rhythm of heating and cooling, light and dark, that would later become one of the fundamental environmental oscillations driving biological evolution.

Second, it stabilized Earth’s axial tilt. Without the Moon’s gravitational influence, Earth’s obliquity would wander chaotically over millions of years, driven by gravitational perturbations from Jupiter and the other planets. Mars, which has no large moon, shows exactly this behavior: its axial tilt has varied between roughly 10 and 60 degrees over geological time. Earth’s tilt, pinned near 23.5 degrees by the Moon, gives us stable, predictable seasons. This matters less for the origin of life and more for its long-term persistence–a world with wildly swinging seasons is a harder place to sustain complex biogeochemical cycles.

Third–and perhaps most importantly–the giant impact stripped away much of Earth’s original atmosphere and resurfaced the planet. Whatever primordial atmosphere the young Earth had accumulated was largely blown off. The atmosphere that grew back was secondary: outgassed from the interior through volcanism and delivered by later impacts. This secondary atmosphere was dominated by carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water vapor–the same gases that, under the right conditions, would become the feedstock for life.

3.3 The divergence: Venus, Earth, and Mars

“Same starting materials, different outcomes” is a slogan until you pin numbers to it.

3.3.1 Venus: the greenhouse that ate itself

Venus today is uninhabitable. Surface temperature: 460 degrees Celsius. Surface pressure: 92 atmospheres–equivalent to being 900 meters underwater on Earth. The atmosphere is 96.5 percent carbon dioxide, with clouds of sulfuric acid. No liquid water exists on the surface or anywhere in the atmosphere where it could persist.

And yet Venus is nearly Earth’s twin in size and mass. It formed from the same part of the solar nebula. It almost certainly received similar amounts of water. There is even suggestive evidence that Venus may have had surface oceans early in its history.

So what happened?

The answer is written in isotopes. When planetary scientists compare the nitrogen, carbon, and oxygen isotope ratios of Venus’s atmosphere to Earth’s, they find striking similarities–consistent with both planets starting from the same mix of volatiles. But one ratio is dramatically different: the deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio (D/H). Venus’s atmosphere has a D/H ratio roughly 100 to 150 times higher than Earth’s.

That ratio records catastrophic water loss. Deuterium (D, or \(^2\)H) is the heavy isotope of hydrogen. It is chemically almost identical to ordinary hydrogen (\(^1\)H) but twice as massive. When water molecules are broken apart in the upper atmosphere by ultraviolet radiation, the lighter \(^1\)H escapes to space more easily than the heavier D. Over time, preferential loss of light hydrogen enriches the remaining hydrogen in deuterium. The more water you lose, the higher the D/H ratio climbs.

Venus’s extreme D/H ratio means it lost nearly all of its hydrogen–and therefore nearly all of its water–to space.

The mechanism is a runaway greenhouse, and it proceeds in steps that are individually straightforward but collectively devastating:

Venus is closer to the Sun than Earth (0.72 AU versus 1.00 AU). By the inverse-square law, it receives about 2,600 W/m\(^2\) of solar flux compared to Earth’s 1,361 W/m\(^2\)—nearly twice as much energy per unit area. At some point in its early history–perhaps when the Sun was slightly brighter, or when some other perturbation tipped the balance–surface temperatures likely crossed a critical threshold—models place it in the range of 70 to 80 degrees Celsius, though the exact value remains debated.

Above that threshold, the oceans began to evaporate massively. Water moved from the surface into the atmosphere:

\[\text{H}_2\text{O}(\ell) \longrightarrow \text{H}_2\text{O}(g)\]

Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas. More water in the atmosphere trapped more infrared radiation, which raised surface temperatures further, which evaporated more water. This is a positive feedback loop–a thermal runaway.

With the oceans now in the atmosphere, solar ultraviolet radiation could reach the water vapor. The net result of UV photolysis was the decomposition of water:

\[2\,\text{H}_2\text{O}(g) \xrightarrow{UV} 2\,\text{H}_2(g) + \text{O}_2(g)\]

(This is the net stoichiometry; the actual mechanism proceeds through OH and H radicals in multiple steps.)

The liberated hydrogen, being the lightest gas, escaped from the top of the atmosphere into space. The oxygen was consumed by reactions with surface rocks and volcanic gases.

With the hydrogen gone, there was no way to reconstitute water. The loss was irreversible.

The entire process may have taken as little as a few hundred million years. By the time it was over, Venus had no water, no ocean, no possibility of the liquid-phase chemistry that life requires. The carbon dioxide that would have dissolved into oceans on a cooler planet remained in the atmosphere instead, thickening the greenhouse blanket further. Venus became what it is today: a cautionary tale written in isotope ratios.

3.3.2 Why Earth kept its water

Earth sits only about 38 percent farther from the Sun than Venus. That modest difference in orbital distance was enough–but just barely–to prevent the same runaway.

The key is what atmospheric scientists call the cold trap. On Earth, the tropopause (roughly 12 km altitude) is very cold: around minus 60 degrees Celsius. At that temperature the saturation vapor pressure of water is only about 1 Pa—orders of magnitude lower than at the surface. Water vapor rising from below condenses and falls back as rain long before it reaches the altitudes where ultraviolet radiation could break it apart. The tropopause acts as a cold lid, trapping water in the lower atmosphere where it is shielded from photolysis.

On Venus, the greater solar flux pushed temperatures high enough that no cold trap could form. Water vapor mixed freely into the upper atmosphere, where UV radiation destroyed it molecule by molecule.

This is a knife-edge. Earth’s cold trap works today, and has worked for most of Earth’s history, but it is not guaranteed by any deep principle. It is a consequence of Earth’s specific distance from the Sun, its atmospheric composition, and its surface temperature. Move Earth 10 to 15 percent closer to the Sun, and models suggest the cold trap fails, the runaway begins, and we join Venus.

Same physics. Same starting materials. A difference of a few tens of millions of kilometers–less than a third of the distance from the Earth to the Sun–and the outcome is a lifeless furnace versus a habitable world.

3.3.3 Mars: the planet that lost its shield

Mars tells the opposite cautionary tale. Where Venus got too hot and lost its water upward, Mars got too cold and lost its atmosphere outward.

Mars is smaller than Earth–about half the diameter, roughly one-tenth the mass. Its lower mass meant lower internal heat, which meant its core cooled faster, which meant it lost its global magnetic field earlier. Without a magnetic field, the solar wind–a stream of charged particles from the Sun–could interact directly with the upper atmosphere, stripping it away molecule by molecule over hundreds of millions of years.

As the atmosphere thinned, surface pressure dropped. Mars’s present-day surface pressure is about 610 Pa—0.6 percent of Earth’s. Models suggest it may have started with 0.5 to 1 bar or more; the loss unfolded over hundreds of millions of years as the dynamo faded. Below a certain pressure, liquid water cannot exist regardless of temperature: it either freezes or sublimes directly to vapor. Mars crossed that threshold and its surface water was lost–some to space, some frozen into the regolith and polar caps, some perhaps trapped in subsurface reservoirs that remain liquid (under pressure, in contact with salts) even today.

But here is the tantalizing part: early Mars may have been habitable.

During the Hadean eon–the same period when Earth was being pummeled by giant impacts and was arguably less hospitable than it would later become–Mars may have had a thicker atmosphere, warmer surface temperatures, and liquid water flowing on its surface. The evidence is geological: river valleys, lake beds, and mineral deposits that require sustained liquid water to form. Some of these features date to 4.0 to 3.7 billion years ago.

The implication is startling. During the window when life first appeared on Earth (somewhere between 4.0 and 3.5 billion years ago), Mars may have been an equally plausible–perhaps even safer–cradle for life. Mars had liquid water. It had the same basic chemistry. And it may have been less violent than Earth, which was still being heavily bombarded.

This raises a possibility that planetary scientists take seriously: that life may have originated on Mars and been transported to Earth inside meteorites blasted off the Martian surface by impacts. We know that Martian meteorites reach Earth–we have them in our collections. We know that some bacteria can survive the conditions of ejection, transit through space, and atmospheric entry. The hypothesis is unproven, but it is not fringe science. It is a direct consequence of the fact that the same chemistry was available on two neighboring planets during the same time window.10

3.4 The first ocean

Wherever life originated, it needed liquid water. Not as a decorative feature, but as a physical requirement: water is the solvent in which biochemical reactions occur, the medium through which reactants diffuse to meet each other, and a participant in countless hydrolysis and condensation reactions. Without liquid water, the thermodynamic rules from Chapter 1 are real but irrelevant–there is no medium in which to run the chemistry.

The evidence that Earth’s hydrosphere appeared very early comes from those ancient zircon crystals mentioned above. Zircons (zirconium silicate, ZrSiO\(_4\)) are extraordinarily durable minerals. They resist weathering, metamorphism, and even partial melting of the rocks that contain them. Some zircon crystals from the Jack Hills of Western Australia have been dated to 4.4 billion years ago–only about 150 million years after the Earth formed.11

The structure and oxygen isotope composition of these zircons suggest that they crystallized from magma that had interacted with liquid water. Specifically, the oxygen isotope ratios (\(\delta^{18}\)O values) are higher than what you would expect from a purely magmatic origin, consistent with the incorporation of water-altered material into the melt. This is not proof of a surface ocean–but it is strong evidence that liquid water was present on or near the Earth’s surface within the first few hundred million years.

If the ocean existed that early, then the stage for life was set far sooner than the violent Hadean imagery might suggest. Even while the planet was still being bombarded, even while the surface may have been repeatedly sterilized by large impacts, water was there–cycling between the surface and the interior, dissolving minerals, and accumulating the dissolved inventory that would become the raw material for biochemistry.

3.4.1 An exotic soup

The early ocean was not like the modern ocean. It was hotter–perhaps 60 to 80 degrees Celsius according to isotope proxies, though estimates vary. It was more acidic, with a lower pH driven by dissolved carbon dioxide. And it was chemically richer in ways that matter for biology.

The ancient ocean was laden with dissolved metals that are rare in today’s seawater: tungsten, molybdenum, vanadium, nickel, cobalt, iron in soluble form. These are not arbitrary trace elements. They are the metals that sit at the active sites of the oldest enzymes–the metalloprotein cofactors that catalyze the most fundamental biochemical reactions.12

This is not a coincidence. It is a fossil written in protein structure. Many of the enzymes that drive the most ancient metabolisms–nitrogen fixation, hydrogen metabolism, carbon fixation in methanogens and acetogens–use metal cofactors that seem oddly exotic by the standards of modern seawater chemistry. Molybdenum in nitrogenase. Tungsten in some archaeal enzymes. Nickel in methyl-coenzyme M reductase. Iron-sulfur clusters in nearly everything ancient.

The explanation is straightforward: life’s earliest enzymes evolved in an ocean where these metals were available. As the ocean chemistry changed over billions of years–as oxygen accumulated and changed the solubility of various metals, as sulfide precipitation removed others–the enzymes kept their original metal requirements. Proteins are conservative. They do not easily swap one metal for another, because the entire geometry of the active site is built around a specific ion. The result is that modern organisms still require trace amounts of metals that were abundant in the Hadean ocean but are scarce today. Biology remembers what geology has forgotten.

3.5 The first signatures of life

When did life actually appear? The honest answer is: we are not certain, because the earliest evidence is indirect and debated. But the best current evidence points to life being present on Earth by at least 3.8 billion years ago, and possibly earlier.

The evidence comes from Greenland. In the Isua supracrustal belt of southwestern Greenland, rocks dating to approximately 3.8 billion years old contain grains of apatite (calcium phosphate) with tiny inclusions of graphite. That graphite has a carbon isotope composition that is difficult to explain without biology.13

Here is how the argument works. Carbon has two stable isotopes: \(^{12}\)C (six protons, six neutrons, about 98.9 percent of all carbon) and \(^{13}\)C (six protons, seven neutrons, about 1.1 percent). When organisms fix carbon dioxide into organic matter–when they build biomass from CO\(_2\)–the enzymes involved (particularly RuBisCO in modern autotrophs) preferentially incorporate the lighter isotope, \(^{12}\)C. This is not a choice; it is a consequence of the slightly lower activation energy for reactions involving the lighter isotope. The result is that biogenic organic matter is enriched in \(^{12}\)C relative to the CO\(_2\) it came from, and the residual inorganic carbon (in carbonates, for instance) is correspondingly enriched in \(^{13}\)C.

The graphite inclusions in the Isua apatite grains show exactly this signature: an enrichment in \(^{12}\)C consistent with biological carbon fixation. The magnitude of the enrichment–typically expressed as \(\delta^{13}\)C values of roughly $-$20 to $-$30 per mil relative to a standard–falls squarely within the range produced by autotrophic organisms.14

This is not the only possible interpretation. Abiotic processes can also fractionate carbon isotopes, although typically not to the same degree or with the same consistency. The debate continues.15 But the Isua signature, combined with similar findings from other early Archean localities, forms a coherent picture: by 3.8 billion years ago, something on Earth was fixing carbon from CO\(_2\) into organic matter, using the same isotopic discrimination that biological enzymes produce today.

If life was already fixing carbon by 3.8 billion years ago, then the origin of life must have occurred even earlier–during the Hadean, during the bombardment, during the period from which we have almost no rock record. The stage was set, and the actors appeared almost as soon as the stage was habitable. The geological time scale that frames this story has been refined over decades of stratigraphic and geochronologic work.16

3.6 The cooling planet

Life did not appear on a world like ours. It appeared on a world that was significantly hotter, and it has been adapting to a cooling planet ever since.

The most striking evidence for this comes from an ingenious approach: resurrecting ancient proteins. Eric Gaucher and colleagues reconstructed the likely amino acid sequences of ancestral elongation factors–proteins involved in translation, the process by which ribosomes read messenger RNA and build proteins. Because elongation factors are universal (present in all domains of life) and essential (you cannot live without them), their phylogenetic tree extends deep into evolutionary history.17

By reconstructing these ancestral proteins in the laboratory and measuring their thermal stability, Gaucher’s team inferred the temperatures at which the organisms carrying those proteins likely lived. The results trace a clear cooling trend:

- The earliest common ancestors, dating to the early Archean (roughly 3.5 billion years ago), appear to have preferred temperatures of approximately 60 to 70 degrees Celsius–solidly thermophilic.

- By the late Proterozoic (roughly 500 million years ago), the preferred temperatures had dropped to approximately 35 to 37 degrees Celsius–close to the body temperature of modern mammals.

This 30-degree cooling over three billion years is independently supported by oxygen isotope records from marine sediments, which show a similar trend.18

The implication for our story is this: the earliest life was not just tolerant of heat. It was adapted to heat, because the planet was hot. The first microbes were thermophiles or even hyperthermophiles–organisms whose enzymes worked best at temperatures that would cook most modern life. As the planet cooled, life followed the temperature downward, adapting its proteins step by step to progressively cooler conditions.

This illustrates the non-equilibrium theme from Chapter 1. Life does not set the temperature. The planet sets the temperature, and life adapts its machinery to harvest energy within whatever temperature regime it finds. The thermodynamic rules do not change–\(\Delta G\) is \(\Delta G\) whether the water is 70 degrees or 35 degrees–but the kinetic landscape changes profoundly, and with it the strategies that pay off.

How do we know the temperature of an ocean that evaporated three billion years ago? How do we detect the breath of organisms that left no fossils? The answer, in almost every case, is isotopes.

Different physical and biological processes fractionate isotopes–preferring lighter or heavier versions of the same element–in predictable ways. By measuring isotope ratios in ancient minerals, we can reconstruct conditions that no instrument ever recorded.

Carbon isotopes and the signature of life. The carbon isotope ratio \(\delta^{13}\)C is the workhorse proxy for ancient biological activity. Autotrophic organisms preferentially fix \(^{12}\)C from CO\(_2\), leaving the residual inorganic carbon pool enriched in \(^{13}\)C. A persistent offset between carbonate \(\delta^{13}\)C and organic carbon \(\delta^{13}\)C in the sedimentary record–maintained for over 3.5 billion years–is one of the strongest lines of evidence that life has been continuously active on Earth since the early Archean.19

Oxygen isotopes as a thermometer. When organisms build calcium carbonate shells (or when carbonate precipitates abiotically), the \(^{18}\)O/\(^{16}\)O ratio of the mineral depends on temperature. Colder water produces carbonate with higher \(\delta^{18}\)O. This relationship has been calibrated in modern organisms and applied, with appropriate caution, to ancient carbonates to reconstruct ocean temperatures spanning hundreds of millions of years.

Trace element ratios in biominerals. Beyond isotopes, the chemical composition of biogenic minerals carries environmental information:

- Sr/Ca ratios in mollusk shells have been used as proxies for El Nino events, because Sr incorporation into aragonite varies with temperature and growth rate.20

- Mg/Ca ratios in foraminiferal calcite serve as temperature proxies, though the relationship is complicated by biological controls on biomineralization. Recent work has developed new models for how trace elements are incorporated into foraminiferal tests.21

- Shell nanostructure: the ultrastructure of nacre (mother-of-pearl) in mollusk shells correlates with the temperature and pressure conditions during growth, providing yet another independent environmental record.22

Goethite and ancient CO\(_2\). One of the more remarkable proxy systems involves goethite (\(\alpha\)-FeOOH), an iron oxyhydroxide mineral that forms during weathering. Carbon from atmospheric CO\(_2\) is incorporated into goethite during its formation, and the carbon isotope composition of this trapped carbon reflects the CO\(_2\) concentration of the atmosphere at the time of mineral formation.

Yapp and colleagues established a quantitative relationship between the carbon isotope composition of goethite-hosted carbonate and the mole fraction \(X\) of CO\(_2\) in soil gas:23

\[\delta^{13}\text{C} = \frac{0.0162}{X} - 20.1\]

This relationship, with a correlation coefficient of \(r = 0.98\), has been validated against independent measurements.24 Combined with the relationship between soil CO\(_2\) mole fraction and atmospheric partial pressure:25

\[P_{\text{CO}_2} = \log(X) + 6.04 - \frac{1570}{T}\]

and an independent estimate of paleotemperature (from oxygen isotopes, for instance), one can estimate the atmospheric CO\(_2\) concentration at the time the goethite formed. This approach has provided some of the best constraints on Phanerozoic CO\(_2\) levels.

The common thread across all these proxies is the same: physical and chemical processes leave isotopic fingerprints, and those fingerprints are preserved in minerals that survive for billions of years. The diary is not easy to read–each proxy has assumptions, calibration uncertainties, and potential for alteration after deposition. But taken together, these proxies give us a remarkably detailed picture of conditions on a planet that left almost no other record of its youth.

3.7 The inventory, assembled

By roughly 4 billion years ago–perhaps earlier–the Earth had assembled a remarkable inventory. Consider what was in place:

Liquid water, cycling between ocean, atmosphere, and crust, providing the solvent and reaction medium that aqueous chemistry requires.

An atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide and nitrogen, with trace amounts of methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and other reduced gases from volcanic outgassing. This atmosphere was not oxidizing (there was virtually no free oxygen), which is important because many of the chemical reactions that build biological molecules are more favorable under reducing conditions.

Dissolved metals–iron, nickel, molybdenum, tungsten, cobalt, manganese, vanadium–available in the ocean at concentrations far higher than today. These would become the catalytic hearts of the first enzymes.

Energy sources: sunlight (ultraviolet radiation was particularly intense, since there was no ozone layer to block it), geothermal heat from a planet still cooling from accretion, chemical energy from the interaction of water with freshly exposed rock (serpentinization reactions that produce hydrogen gas), and electrical energy from lightning.

Temperature: hot by modern standards (perhaps 60 to 80 degrees Celsius in the ocean according to isotope proxies, likely higher near hydrothermal vents), but within the range where organic chemistry can proceed and where proteins, once they exist, can fold and function.

A day-night cycle and seasons, courtesy of the Moon-forming impact, providing environmental oscillations that drive mixing, temperature cycling, and periodic changes in light availability.

Geological recycling: plate tectonics (or some proto-tectonic process) cycling material between the surface and the interior, preventing the planet from reaching a static chemical equilibrium. This is critical. A planet that stops recycling its crust eventually reaches a surface chemistry equilibrium and becomes geochemically dead. Earth’s tectonics have kept the surface out of equilibrium for over four billion years–providing a continuous supply of reduced material from the mantle to the oxidized surface.

Every item on this list is physical. Every one is measurable. And every one distinguishes Earth from its two nearest neighbors: Venus lost its water, Mars lost its atmosphere, and neither maintained the geological recycling that keeps the chemical gradients fresh.

3.8 Same rules, one stage

The laws of thermodynamics operate everywhere. The quantum mechanics that determines bond energies and reaction rates is the same on Venus, Earth, and Mars. Gibbs free energy is Gibbs free energy whether you calculate it for a reaction in Earth’s ocean or in a hypothetical Martian puddle.

But laws alone do not produce outcomes. You also need conditions: the right temperature range, the right solvent, the right inventory of elements in accessible forms, the right energy sources, and–crucially–enough time for the slow, improbable process of chemical evolution to produce self-replicating systems.

Earth provided all of these. Not because it was designed to, and not because rocky planets commonly do. Earth provided them because of a specific sequence of physical accidents: the right distance from the Sun (preserving the cold trap), a giant impact (giving it a stabilizing moon and a secondary atmosphere), the right mass (retaining atmosphere but allowing tectonic recycling), and an ocean that appeared early and persisted.

Venus shows what happens when the distance is wrong. Mars shows what happens when the mass is wrong. Both had water. Both had carbon. Both had the same thermodynamic rules. Neither became a living world.

The stage is set: a warm, wet, metal-rich, geologically active planet bathed in energy, with the thermodynamic rules of Chapter 1 operating in every drop of its ancient ocean.

And at the bottom of that ocean, hydrothermal vents are already pumping hydrogen gas and carbon monoxide into warm, metal-rich water—an environment saturated with the electron donors and carbon sources that will underwrite the first microbial metabolisms. If thermodynamic models and recent vent-fluid analyses are right, trace hydrogen cyanide is in the mix as well.26 The thermodynamics are favorable. The raw materials are abundant. The planet has time. What it does not yet have is a molecule that can copy itself.

3.9 Takeaways

- Earth, Venus, and Mars formed from the same solar nebula with similar starting chemistry. The divergence in their fates was driven by physical parameters: orbital distance, planetary mass, and the presence or absence of a large moon.

- Venus lost its water through a runaway greenhouse, recorded in its extreme deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio. Earth’s cold trap–a consequence of its greater distance from the Sun–prevented the same catastrophe.

- Mars lost its atmosphere to solar wind stripping after its magnetic field died, a consequence of its smaller mass and faster core cooling.

- Earth’s ocean appeared within the first few hundred million years, as recorded by 4.4-billion-year-old zircon crystals from Western Australia.

- The early ocean was rich in dissolved metals (tungsten, molybdenum, nickel, iron) that became the catalytic cores of the first enzymes–a chemical memory preserved in modern protein structures.

- The earliest isotopic evidence of life (carbon isotope fractionation in 3.8-billion-year-old graphite from Greenland) indicates that biological carbon fixation was occurring by the early Archean.

- Resurrected ancestral proteins indicate that the earliest organisms preferred temperatures of 60 to 70 degrees Celsius; the planet has been cooling, and life has been adapting, for over three billion years.

Abigail C. Allwood et al., “Stromatolite Reef from the Early Archaean Era of Australia,” Nature 441 (2006): 714–718. Evidence of microbial communities at 3.43 Ga. (Allwood et al. 2006)↩︎

Simon A. Wilde et al., “Evidence from Detrital Zircons for the Existence of Continental Crust and Oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr Ago,” Nature 409 (2001): 175–178. Jack Hills zircons dated to 4.4 Ga with oxygen isotope signatures suggesting liquid water interaction. (Wilde et al. 2001)↩︎

Eric A. Gaucher et al., “Palaeotemperature Trend for Precambrian Life Inferred from Resurrected Proteins,” Nature 451 (2008): 704–707. Ancestral protein reconstruction suggests early Archean organisms preferred 60–70°C. (Gaucher, Govindarajan, and Ganesh 2008)↩︎

Thomas M. Donahue et al., “Venus Was Wet: A Measurement of the Ratio of Deuterium to Hydrogen,” Science 216 (1982): 630–633. The D/H ratio in Venus’s atmosphere is ~150× Earth’s, indicating catastrophic water loss. (Donahue et al. 1982)↩︎

Michael J. Way et al., “Was Venus the First Habitable World of Our Solar System?” Geophysical Research Letters 43 (2016): 8376–8383. Models suggest Venus may have had surface liquid water until 715 Ma. (Way et al. 2016)↩︎

Mario H. Acuña et al., “Global Distribution of Crustal Magnetization Discovered by the Mars Global Surveyor MAG/ER Experiment,” Science 284 (1999): 790–793. Crustal magnetic remnants indicate Mars lost its global dynamo early. (Acuña et al. 1999)↩︎

James W. Head III and Bethany L. Carr, “The Noachian Epoch on Mars,” Journal of Geophysical Research 115 (2010): E03005 (Carr and Head 2010); Robin Wordsworth et al., “Comparison of ‘Warm and Wet’ and ‘Cold and Icy’ Scenarios for Early Mars in a 3-D Climate Model,” Journal of Geophysical Research 120 (2015): 1201–1219. (Wordsworth 2016)↩︎

Simon A. Wilde et al., “Evidence from Detrital Zircons for the Existence of Continental Crust and Oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr Ago,” Nature 409 (2001): 175–178. (Wilde et al. 2001)↩︎

Robin M. Canup and Erik Asphaug, “Origin of the Moon in a Giant Impact Near the End of the Earth’s Formation,” Nature 412 (2001): 708–712. (Canup and Asphaug 2001)↩︎

The hypothesis of panspermia from Mars to Earth is discussed in Alexandr Markov, Birth of Complexity: Evolutionary Biology Today: Unexpected Discoveries and New Questions (2010). Experimental work on bacterial survival in space bolsters the plausibility. (Markov 2010)↩︎

Simon A. Wilde et al., “Evidence from Detrital Zircons for the Existence of Continental Crust and Oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr Ago,” Nature 409 (2001): 175–178. (Wilde et al. 2001)↩︎

Christophe L. Dupont et al., “History of Biological Metal Utilization Inferred through Phylogenomic Analysis of Protein Structures,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (2010): 10567–10572. (Dupont et al. 2010)↩︎

Manfred Schidlowski, “A 3,800-Million-Year Isotopic Record of Life from Carbon in Sedimentary Rocks,” Nature 333 (1988): 313–318. (Schidlowski 1988)↩︎

The δ¹³C values of −20 to −30‰ in Isua graphite are consistent with RuBisCO-mediated carbon fixation. Manfred Schidlowski, “A 3,800-Million-Year Isotopic Record of Life from Carbon in Sedimentary Rocks,” Nature 333 (1988): 313–318. (Schidlowski 1988)↩︎

The Isua biosignature interpretation remains contested. See Aivo Lepland et al., “Questioning the Evidence for Earth’s Earliest Life—Akilia Revisited,” Geology 33 (2005): 77–79 (Lepland et al. 2005); and Mark A. van Zuilen, Aivo Lepland, and Gustaf Arrhenius, “Reassessing the Evidence for the Earliest Traces of Life,” Nature 418 (2002): 627–630. (Zuilen, Lepland, and Arrhenius 2002)↩︎

Felix M. Gradstein et al., A Geologic Time Scale 2004 (Cambridge University Press, 2004). (Gradstein et al. 2004)↩︎

Eric A. Gaucher et al., “Palaeotemperature Trend for Precambrian Life Inferred from Resurrected Proteins,” Nature 451 (2008): 704–707. (Gaucher, Govindarajan, and Ganesh 2008)↩︎

The cooling trend is supported by multiple independent proxies. Eric A. Gaucher et al., “Palaeotemperature Trend for Precambrian Life Inferred from Resurrected Proteins,” Nature 451 (2008): 704–707. (Gaucher, Govindarajan, and Ganesh 2008)↩︎

Manfred Schidlowski, “A 3,800-Million-Year Isotopic Record of Life from Carbon in Sedimentary Rocks,” Nature 333 (1988): 313–318. The persistent 25–30‰ offset between organic and inorganic carbon through 3.5+ billion years of the sedimentary record is one of the most robust biosignatures. (Schidlowski 1988)↩︎

Alberto Pérez-Huerta et al., “El Niño Impact on Mollusk Biomineralization—Implications for Trace Element Proxy Reconstructions and the Paleo-Archaeological Record,” PLoS ONE 8 (2013): e54274. (Pérez-Huerta et al. 2013)↩︎

Gernot Nehrke et al., “A New Model for Biomineralization and Trace-Element Signatures of Foraminifera Tests,” Biogeosciences 10 (2013): 6759–6767. (Nehrke et al. 2013)↩︎

Ian C. Olson et al., “Mollusk Shell Nacre Ultrastructure Correlates with Environmental Temperature and Pressure,” Journal of the American Chemical Society 134 (2012): 7351–7358. (Olson et al. 2012)↩︎

Crayton J. Yapp and Harald Poths, “Ancient Atmospheric CO₂ Pressures Inferred from Natural Goethites,” Nature 355 (1992): 342–344 (Yapp and Poths 1992); Crayton J. Yapp, “The Abundance of Fe(CO₃)OH in Goethite,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 60 (1996): 4905–4916 (Yapp 1996); Crayton J. Yapp and Harald Poths, “Carbon Isotopes in Continental Weathering Environments and Variations in Ancient Atmospheric CO₂ Pressure,” Earth and Planetary Science Letters 137 (1996): 71–82. (Yapp and Poths 1996)↩︎

Paul A. Schroeder and Nathan D. Melear, “Stable Carbon Isotope Signatures Preserved in Authigenic Gibbsite from a Forested Granitic Regolith: Panola Mt., Georgia, USA,” Geoderma 91 (1999): 59–76. (Schroeder and Melear 1999)↩︎

Crayton J. Yapp, “Oxygen and Hydrogen Isotope Variations among Goethites (α-FeOOH) and the Determination of Paleotemperatures,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 51 (1987): 355–364. (Yapp 1987)↩︎

H\(_2\) and CO in vent fluids are well established. HCN at vents is thermodynamically predicted and has been detected in some fluid analyses; see Niklas G. Holm and Astrid Neubeck, “Reduction of Nitrogen Compounds in Oceanic Basement and Its Implications for HCN Formation and Abiotic Organic Synthesis,” Geochemical Transactions 10 (2009): 9 (Holm and Neubeck 2009); for prebiotic chemistry context, John D. Sutherland, “The Origin of Life—Out of the Blue,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition 55 (2016): 104–121. (Sutherland 2016)↩︎