4 Spark

Imagine you find a book.

Not an ordinary book – this one is written in a language you have never seen, and the ink is a protein that degrades unless it is continuously recopied by a machine. The machine, in turn, is built from instructions contained in the book. Without the machine, the book decays. Without the book, the machine cannot be assembled. Each depends entirely on the other, and neither can exist first.

This is the central paradox of the origin of life, and for decades it stopped the conversation cold.

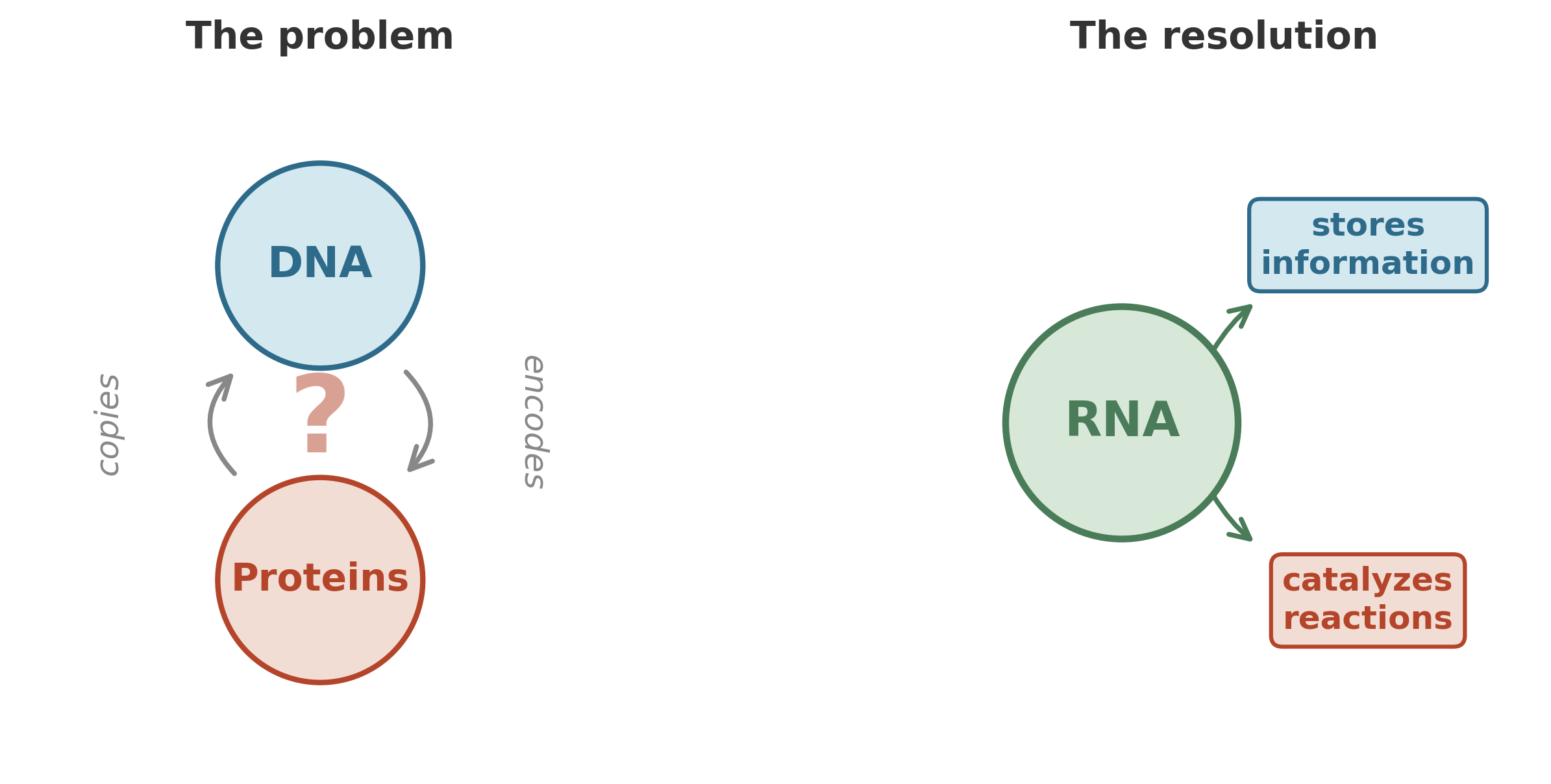

In modern cells, the division of labor is clean. DNA stores the instructions. Proteins do the work – catalyzing reactions, building structures, transporting molecules across membranes. But proteins cannot copy themselves; they need DNA’s blueprint. And DNA cannot do anything useful without the proteins that read it, unwind it, and replicate it. Which came first? The question is not rhetorical. It is a genuine engineering bottleneck: you cannot bootstrap a system that requires two specialized components if each component depends on the other for its existence.

The answer, when it arrived, came from an unexpected direction. It came from the molecule that everyone had dismissed as a mere intermediary.

4.1 The middleman steps forward

RNA sits between DNA and proteins in every modern cell. It carries the genetic message from the archive (DNA) to the factory floor (ribosomes, which are themselves largely made of RNA). For most of the twentieth century, RNA appeared to be a passive carrier – important, but not the molecule doing the work.

Then, in the early 1980s, Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman independently discovered that certain RNA molecules could catalyze chemical reactions.1 They were not just carrying information; they were doing chemistry. These catalytic RNAs were named ribozymes, and their discovery earned Cech and Altman the Nobel Prize in 1989.2

The implications were enormous. If RNA can both store information and catalyze reactions, then you do not need two separate systems to get life started. You need one. A single type of molecule that reads itself and copies itself – an autocatalytic loop of replicating RNA, ribozymes catalyzing the synthesis of copies of themselves.3

This is the RNA world hypothesis: the proposal that the earliest life on Earth was not built from DNA and proteins, but from RNA alone – organisms without the division of labor that modern cells take for granted. The chicken-and-egg paradox dissolves, because RNA is both the chicken and the egg.

The standard RNA alphabet is small: four nucleotides – adenosine (A), guanosine (G), cytidine (C), and uridine (U) – plus a handful of modified variants like inosine.45 With just these letters, RNA can fold into elaborate three-dimensional shapes, creating pockets and surfaces that behave like primitive enzymes. Not as efficient as proteins, not as stable as DNA, but enough. Enough to get the process started.

4.2 Where it happened

Where did RNA chemistry first ignite? Two settings are plausible, and they are not mutually exclusive. Ice can concentrate dilute reactants into tiny liquid pockets between crystals, bringing RNA precursors together at effective concentrations far higher than open water – and many ribozymes work best at low temperatures.6 Hydrothermal vents, meanwhile, provide a continuous supply of reduced gases (CO, H\(_2\), HCN) and metal catalysts (iron, nickel) at temperatures where abiotic organic synthesis proceeds readily.78 The cold scenario is strong on the first spark – concentrating molecules for the initial assembly of self-copying RNA – but weak on sustained supply. The hot scenario is strong on raw materials but weak on the delicate chemistry of RNA folding. It is possible that different steps happened in different settings: building blocks synthesized at vents, transported by currents to colder environments where replication proceeded more efficiently. The planet is large, and chemistry does not respect the boundaries of human narratives.

4.3 The phosphorus problem

Before RNA can copy itself, RNA must exist. And building RNA from scratch requires something that the early Earth did not obviously have in abundance: phosphorus.

RNA’s backbone is not made of the nucleotide bases themselves. The bases are the informational part – the letters. The backbone, the structural spine that holds the letters in order, is a chain of sugar molecules linked by phosphate bridges. Without phosphate, there is no polymer. Without a polymer, there is no information storage. The RNA world hypothesis requires an early habitat rich in reactive phosphorus.9

Where did it come from? In 2005, Matthew Pasek and Dante Lauretta proposed a striking answer: iron meteorites.10

The early Earth was under heavy bombardment.11 Meteorites arrived constantly, and among them were iron-rich bodies containing the mineral schreibersite – an iron-nickel phosphide.12 When schreibersite corrodes in water, it releases reactive phosphorus compounds. Not the stable, locked-up phosphorus of terrestrial rocks, but forms that can participate in organic chemistry. Pasek and Lauretta showed that this corrosion proceeds readily in aqueous conditions, providing a “highly reactive source of prebiotic phosphorus on the surface of the early Earth.”13

The chemistry of life did not arise in isolation from geology. Meteorites provided phosphorus. Minerals provided surfaces. The ocean provided the solvent. Life did not invent its raw materials; it inherited them from the planet’s early bombardment.

4.4 An ocean laced with metal

The ancient ocean was a different solvent than the one we know. It was richer in dissolved heavy metals – not just iron, which was abundant in a world without free oxygen to rust it out of solution, but also more exotic elements: tungsten, molybdenum, vanadium.1415

This matters because many of the enzymes that drive modern biochemistry are not pure protein. They are metalloproteins – protein molecules with metal ions at their active sites, performing the actual catalytic work.16 The protein provides the scaffold; the metal does the chemistry. Strip the iron from a cytochrome, the molybdenum from a nitrogenase, the nickel from a urease, and you have a beautifully folded but catalytically dead molecule.

Why would proteins evolve to depend on metals? One compelling answer is that they did not “choose” metals – they inherited them. In the earliest stages of chemical evolution, before proteins existed, the catalysts were the metals themselves. Iron-sulfur clusters, nickel surfaces, molybdenum compounds – these inorganic materials can catalyze many of the same reactions that enzymes catalyze today, just less efficiently.17

The transition from mineral catalyst to protein catalyst was gradual.18 The first proteins, clumsy and short, would have naturally incorporated iron atoms from their iron-rich environment. Those that happened to fold around a metal ion in a useful way gained a catalytic advantage. Over time, proteins became better scaffolds for the metals, and the metals became more precisely positioned within the proteins. But the metals came first. The proteins grew around them like a house built around a hearth.19

At least one modern organism may preserve this ancient iron-dependent metabolism almost unchanged. Ferroplasma acidiphilum, discovered in 2000 in a metallurgical bioreactor in Tula, Russia, powers itself entirely by oxidizing ferrous iron – its proteins are unusually iron-rich, and its lifestyle closely matches the conditions of the early Earth’s iron-rich, anoxic ocean.20 21 (See Appendix E for more on Ferroplasma.)

One useful tool for thinking about energy content is the Nominal Oxidation State of Carbon (NOSC) – a single number that estimates how much energy is locked in an organic molecule, from fully reduced (methane, NOSC = \(-4\)) to fully oxidized (CO\(_2\), NOSC = \(+4\)). The full framework, developed by LaRowe and Van Cappellen,22 is in Appendix A.

4.5 In the beginning, there was the community

Now we arrive at the most important idea in this chapter. It is also the most counterintuitive.

We have been telling the origin story as if it were about a single lineage: first RNA, then proteins, then DNA, then cells. A lonely molecule in a puddle, gradually becoming more complex. This is the popular version, and it captures something real. But it misses the deepest constraint.

Consider what a living system actually does. It takes in raw materials, transforms them, and produces waste. If it is the only living system around, it will eventually exhaust its raw materials or drown in its own waste. This is not a biological problem; it is a thermodynamic one. A single organism, running a single metabolic strategy, cannot sustain itself indefinitely in a closed environment. It would be, as Markov puts it, “as impossible as a perpetual motion machine.”23

The stable existence of any biosphere – even the most primitive one – requires relatively closed biogeochemical cycles. Resources must be recycled. One organism’s waste must become another organism’s food. The carbon that is fixed must eventually be re-oxidized. The sulfate that is reduced must eventually be re-oxidized. The cycle must close, or the system runs down.

A single type of organism cannot close these cycles alone.

There is one narrow theoretical exception: an organism that happens to catalyze reactions that are already part of established geochemical cycles. Such a creature would not need a partner, because the planet itself would serve as its recycling system – food trickling in from geological sources, waste absorbed back into geological sinks. This is plausible only for the simplest metabolisms, and even then, it works only if the organism’s demands are modest enough to be met by geological supply.24

But for anything more ambitious – for life that grows, diversifies, and reshapes its environment – cooperation is not an optional add-on. It is a structural requirement from the very beginning.

This is a radical departure from the popular narrative. In the standard story, life begins as a solitary replicator and only later learns to cooperate. The biogeochemical argument reverses the order: the community came first, not because cooperation is noble, but because thermodynamics demands it. A single metabolic strategy, running alone, is a dead end. Multiple strategies, running together and recycling each other’s waste, are a cycle. And cycles can persist.

The earliest communities may have been simple. Perhaps methanogenic archaea reduced CO\(_2\) to CH\(_4\) using hydrogen, while other organisms oxidized the methane or consumed other waste products. Perhaps sulfate reducers and sulfur oxidizers formed the first recycling pair. The details are debated and may never be fully resolved. But the principle is clear: life’s first achievement was not the individual cell. It was the network.

4.6 The circuit redrawn

We can see this through the lens we built in the first two chapters. Think of the earliest biosphere as a primitive electrical circuit.

Each metabolic type is a different wire connecting a different pair of terminals. Methanogens connect the CO\(_2\)/CH\(_4\) couple. Sulfate reducers connect the SO\(_4^{2-}\)/H\(_2\)S couple. Iron oxidizers connect the Fe\(^{2+}\)/Fe\(^{3+}\) couple. No single wire carries enough current to matter for long. But wire them together – let the products of one reaction become the reactants of another – and you get a circuit with multiple loops. Current flows continuously, because every product has somewhere to go.

This is what “community” means in thermodynamic terms. It is not a word about feelings or altruism (though those will come later). It is a word about closing circuits. About making sure that the electrons, once moved, have a path back to the beginning.

And this is why, when we eventually find the oldest unambiguous traces of life in the rock record – the layered structures called stromatolites, dating back more than 3.4 billion years25 – we do not find evidence of a single organism. We find evidence of a community.26 A layered, multi-species mat of cooperating microbes, each occupying a different niche, each performing a different metabolic trick, and each depending on the others to keep the cycles turning.

4.7 From spark to city

The chapter began with a paradox: the chicken and the egg, information and machinery, locked in mutual dependence. RNA resolved that paradox by being both at once. But RNA alone does not make a biosphere. A biosphere requires energy capture, waste recycling, and the closing of biogeochemical cycles – and that requires a community.

The next question is: what did those first communities look like? How did they organize themselves physically? And how did their organization shape the planet?

The answer lies in the most successful architecture in the history of life: the microbial mat. Layered cities of cooperating microbes, stacked by function, connected by chemistry, that ruled the Earth for billions of years before anything with a nucleus existed.

The spark has caught. Now it builds.

4.8 Takeaway

- The chicken-and-egg paradox (DNA needs proteins, proteins need DNA) is resolved by RNA, which can store information and catalyze reactions.

- Life may have started cold (ice concentrating reactants), hot (hydrothermal vents providing building blocks), or both in sequence.

- Reactive phosphorus for RNA backbones likely came from iron meteorites corroding in early water.

- Ancient ocean metals (iron, nickel, tungsten, molybdenum) served as the first catalysts; proteins evolved around them.

- Life could not have begun as a single organism running a single metabolism. Biogeochemical cycles require multiple metabolic strategies recycling each other’s waste. The community came first.

Thomas R. Cech, “A Model for the RNA-Catalyzed Replication of RNA,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 83 (1986): 4360-4363. Cech demonstrated that RNA molecules could act as catalysts, performing chemical reactions without protein enzymes. (Cech 1986)↩︎

The 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded jointly to Sidney Altman and Thomas Cech “for their discovery of catalytic properties of RNA.” This discovery resolved the chicken-and-egg problem of the origin of life by showing that RNA could both store information and catalyze reactions. (Cech 1986)↩︎

Kruger et al., Self-splicing RNA: autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena (1982); Gilbert, Origin of life: The RNA world (1986). The first prototype of the future RNA-organism could be the autocatalytic loop formed by replicating RNA molecules – ribozymes, capable of catalyzing the synthesis of copies of themselves. (Kruger et al. 1982; Gilbert 1986)↩︎

Markov (2010). A, G, C, U – the standard nucleotides: adenosine, guanosine, cytidine and uridine; other letters mark nonstandard (modified) nucleotides, including inosine. (Markov 2010)↩︎

The four standard RNA nucleotides (A, G, C, U) differ from DNA only in the sugar backbone (ribose vs. deoxyribose) and the substitution of uracil for thymine. This simpler chemistry may reflect RNA’s evolutionary priority over DNA. (Alberts et al. 2015)↩︎

Attwater et al., In-ice evolution of RNA polymerase ribozyme activity (2013). Many ribozymes work best at low temperatures, sometimes below the freezing point of water. Ice creates tiny cavities with high reactant concentrations, enabling RNA polymerase ribozyme activity at temperatures as low as -19 C. (Attwater, Wochner, and Holliger 2013)↩︎

Adam P. Johnson et al., “The Miller Volcanic Spark Discharge Experiment,” Science 322 (2008): 404. Reanalysis of Stanley Miller’s original 1950s volcanic spark discharge samples revealed a wider variety of amino acids and hydroxylated compounds than reported in Miller’s classic 1953 paper, demonstrating that volcanic lightning conditions could produce diverse organic building blocks. (Johnson et al. 2008)↩︎

Stanley L. Miller, “A Production of Amino Acids Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions,” Science 117 (1953): 528-529. Miller’s famous experiment demonstrated that organic compounds including amino acids could form spontaneously from simple gases (methane, ammonia, hydrogen, water vapor) subjected to electrical discharge, providing early experimental support for abiotic organic synthesis. (Miller 1953)↩︎

Leslie E. Orgel, “Prebiotic Chemistry and the Origin of the RNA World,” Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (2004). Orgel outlined the major steps required to establish an RNA world: sugar synthesis, nucleoside synthesis, phosphorylation, formation of long polynucleotides, and separating and copying double-stranded polynucleotides. (Leslie E 2004)↩︎

Matthew A. Pasek and Dante S. Lauretta, “Aqueous Corrosion of Phosphide Minerals from Iron Meteorites: A Highly Reactive Source of Prebiotic Phosphorus on the Surface of the Early Earth,” Astrobiology (2005). (Pasek and Lauretta 2005)↩︎

The Late Heavy Bombardment (approximately 4.1-3.8 Ga) represents a period of intense meteorite impacts on the inner solar system. This bombardment delivered substantial quantities of volatiles, organics, and reactive minerals including phosphides to the early Earth’s surface. (Pater and Lissauer 2015)↩︎

Schreibersite (Fe,Ni)₃P is a rare terrestrial mineral but common in iron meteorites. Its corrosion in water produces a range of reduced phosphorus compounds including phosphite and hypophosphite, which are far more reactive in prebiotic chemistry than oxidized phosphate minerals. (Pasek and Lauretta 2005)↩︎

Matthew A. Pasek and Dante S. Lauretta, “Aqueous Corrosion of Phosphide Minerals from Iron Meteorites: A Highly Reactive Source of Prebiotic Phosphorus on the Surface of the Early Earth,” Astrobiology (2005). (Pasek and Lauretta 2005)↩︎

Dupont et al., History of biological metal utilization inferred through phylogenomic analysis of protein structures (2010). The ancient ocean contained far more dissolved heavy metals than today, including tungsten, molybdenum, and vanadium. Many protein enzymes use metal ions as essential components (metalloproteins). (Dupont et al. 2010)↩︎

The Archean ocean’s metal content reflected the anoxic atmosphere and reduced state of surface minerals. Without photosynthetic oxygen production, iron remained soluble as Fe²⁺ rather than precipitating as Fe³⁺ oxides, creating dissolved iron concentrations orders of magnitude higher than modern oceans. (Dupont et al. 2010)↩︎

Approximately one-third of all known enzymes require metal cofactors for catalytic activity. The most common are iron, zinc, magnesium, and copper, but molybdenum, tungsten, nickel, and vanadium also play essential roles in specific metabolic pathways. (Dupont et al. 2010)↩︎

Günter Wächtershäuser, “Before Enzymes and Templates: Theory of Surface Metabolism,” Microbiological Reviews 52 (1988): 452-484. The iron-sulfur world hypothesis proposes that life originated on charged mineral surfaces of iron sulfide, where the oxidation of FeS to FeS₂ (pyrite) provided energy for carbon fixation. (Wächtershäuser 1988)↩︎

William Martin and Michael J. Russell, “On the Origins of Cells,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 358 (2003): 59-85. Mineral surfaces, particularly iron-sulfur minerals, can catalyze many of the core reactions of metabolism including carbon fixation and peptide synthesis. (Martin and Russell 2003)↩︎

Dupont et al. (2010). The earliest forms of life actively used simple inorganic catalysts – especially iron and sulfur compounds. Phylogenomic analysis of protein structures shows that the earliest metal-binding domains preferentially bound metals abundant in the Archean ocean, with proteins evolving around pre-existing mineral catalysts. (Dupont et al. 2010)↩︎

Olga V. Golyshina et al., “Ferroplasma acidiphilum gen. nov., sp. nov.,” International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2000). Discovered in a bioreactor at a metallurgical plant in Tula, Russia. (Golyshina et al. 2000)↩︎

Manuel Ferrer et al., “The cellular machinery of Ferroplasma acidiphilum,” Nature (2007). Proposed that Ferroplasma’s iron-rich cellular machinery represents accidentally preserved remnants of ancient life stages. (Ferrer et al. 2007)↩︎

Douglas E. LaRowe and Philippe Van Cappellen, “Degradation of natural organic matter: A thermodynamic analysis,” Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta (2011). (LaRowe and Van Cappellen 2011)↩︎

Markov (2010). “An organism capable alone to close a cycle is not possible, just as a perpetual motion machine.” Stable biosphere requires relatively closed biogeochemical cycles, which a single organism cannot provide. (Markov 2010)↩︎

Markov (2010). “An organism capable alone to close a cycle is not possible, just as a perpetual motion machine.” Stable biosphere requires relatively closed biogeochemical cycles, which a single organism cannot provide. (Markov 2010)↩︎

Abigail C. Allwood et al., “Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia,” Nature 441 (2006): 714-718. The oldest well-preserved stromatolites from the Strelley Pool Formation in Western Australia date to 3.43 Ga and provide morphological and geochemical evidence for photosynthetic microbial communities. (Allwood et al. 2006)↩︎

J. William Schopf, “Fossil Evidence of Archaean Life,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 361 (2006): 869-885. Stromatolites represent fossilized microbial mats – layered communities of bacteria and archaea organized by metabolic function, with photosynthesizers near the surface and anaerobic metabolizers below. (Schopf 2006)↩︎